The program presented on this CD is made up, for the most part, of works seldom played in the world of chamber music for classical guitar, and dedicated to the even rarer formation of the trio. Nevertheless, the aim is to present a repertoire chosen from pieces having in common, beauty and depth of feeling. In order to compose a typical recital program ranging from the Baroque period to the present day, different sources have been used, such as, for example, the transcription technique, ever attentive to the real essence of the work. We have also explored the "historical" repertoire for three guitars, and, lastly, we have introduced new pieces, which enrich the contemporary repertoire for this formation. Furthermore, we consider that the use of three identical guitars made by the same luthier helps to create the sense of listening to one single instrument, in complete accordance with our philosophy of "making music together".

Our program begins with the only work not originally intended for guitar trio: an unusual transcription of the G major Concerto for two mandolins, strings and basso continuo (RV 532) by Antonio Vivaldi (Venice, 1678 - Vienna, 1741). Phenomenal violinist and prolific composer of concertos, the Red Priest wrote this piece for the "figlie di choro", a large instrumental and choral ensemble entirely composed of young girls taken in and educated by the Pio Ospedale della Pietí , a prestigious Venetian orphanage noted for the high quality of the musical education imparted there. Since the Concerto for two mandolins is composed in effect of three real parts, with the violins doubling the solo instruments during the Tutti, the arrangement foresees two guitars for the melodic parts (mandolins and first and second violins), whilst a third instrument is assigned to playing the basso continuo (originally played by a cello and a polyphonic instrument). The concerto bases the structure of its three movements on the principle of a continual search for a strong contrast of sound and is composed in Vivaldi's most typical creative and stylistic vein, defined by Joachim Quantz as "a new genre of musical pieces with magnificent ritornellos". Such a contrast of sound, both harmonic and melodic, is realized magnificently through the continuous dialogue between the two mandolins, moving freely from the brilliant, virtuoso character of the two fast movements to the splendid cantabile of the central Adagio.

Leaving behind the Italian Baroque period, we now move towards the elegant classicism that permeates the Trio Concertant pour trois guitares Op. 29 in D Major by the French composer Antoine L'hoyer (Clermont - Ferrand, 1768 - Paris, 1852). Despite the fact that the figure of L'hoyer received little attention during his lifetime, to be then completely forgotten for over a hundred years, the great artistic value of his recently rediscovered compositions assures his right today to be considered one of the most interesting composers for the guitar of the nineteenth century. The piece is divided into four movements following the archetype of the classical sonata. It opens with a substantial Allegro moderato in sonata form, which rebels against the usual patterns of musical writing for the guitar by searching out, during the development, the most daring harmonies that one could wish. The second movement, on the other hand, is a short Menuetto in E minor with a Da Capo finale, and a poco vivace tempo but with a playful contrasting central Trio in the major key. The third movement is an Adagio molto cantabile, characterised by melodies that are simple and flowing but not lacking in great lyricism. A brilliant Andante with variations closes the whole cycle underlining throughout the six variations all the typical possibilities of the guitar writing of the period. Although the Trio Concertant would seem to be less striking when compared to the virtuoso duets for guitar, they share an excellent instrumental effect, underlining all the qualities of the unusual group of instruments to which it is dedicated. It could be said that here, too, L'hoyer's refined writing arises as a veiled tribute to the great piano composers - Haydn and Mozart - to whom he surely owes his inspiration.

The exquisite composition that Jean-Michel Damase (Bordeaux, 1928) dedicated in 2004 to the guitar trio, takes us to modern-day France, in spite of being devoted to evoking a nostalgic retro mood. Quatre pour trois, in fact, does nothing to hide the deep admiration that Damase professes for the Parisian music of the Belle Époque period and, of course, for its distinguished founders, Debussy, Fauré and Ravel. The charm and elegance of his works remain true to the stylistic tradition learnt at the Paris Conservatoire where his composition studies earned him, at only nineteen years of age, the Prix de Composition and subsequently the prestigious Prix de Rome. The four extremely short bagatelles that make up the work, entitled simply I, II, III, IV, remind us of the tiny musical pieces placed within the eccentric French piano suites. The real difficulty of these short pieces, however, proves to be not so much a technical one as a creative quest among different shades and colours in order to highlight the dialogue between the guitars.

Functioning as a kind of stylistic watershed, the following piece, takes us towards the Central European cultural scene, which developed right at the very beginning of the Twentieth Century. In spite of its small size, the Rondo fur Drei Gitaren by the German composer Paul Hindemith (Hanau, 1895-Frankfurt en Main, 1963) can without doubt be considered one of the masterpieces of the chamber music repertoire for the classical guitar. Conceived as a musical intermezzo, the Rondo was composed in 1925 within the new musical language that Hindemith developed from the 1920's onwards, characterized by a complex contrapuntal style already distant from the Expressionism and late German Romanticism that imbued the works of his youth. This new style found extensive space for research in the music for instrumental groups to which Hindemith dedicated a series of works written between 1922 and 1927, called simply Kammermusik. The mechanicalness of the Rondo, with the aggressive rhythm of its counterpoint and its anti-Romantic "assembly-line" tempo correspond to the ideal of music that found broad confirmation in the Italian artistic movement known as Futurism. It was not by chance that Marinetti, the author of the Manifesto that exalted technology, progress and the dynamism of industry, defined Hindemith, perhaps after having listened to Chamber music, "the leading figure of futurist mechanism".

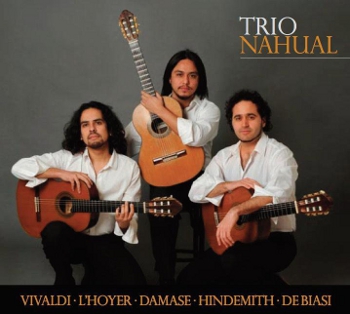

We end the musical journey undertaken in this CD by returning once more to Italy, where we began. Two pieces are now presented written expressly for the Trio Nahual by the young guitarist, composer and painter Marco De Biasi (Vittorio Veneto, 1977). The first piece, Eires (The title is derived from the word "serie" read backwards) is a theme with variations in six sections. The theme, conceived in the vein of a freely treated serialism, is characterised by a captivating melodic line spread between the three guitars. The various thematic units are later taken up and developed in different ways so as to create the five variations that, alternating opposing characters and sound settings between them, range from the South American sounding waltz, to the languid central recitative, to the wild counterpoint of the final variation.

The careful reader will have understood at this point that Eud Eires, as suggested by the title, is in a certain sense, the continuation of the previous piece, therefore "serie due" (second series). The complex formulations that are at the basis of this Fantasia for three guitars, can be found in the studies that the composer carried out on the theories expounded by Kandinsky in his book "The spiritual in Art". In Eud Eires, created at the same time as the painting of the same name, "Eud Eires - rhythmic variations of a painting", De Biasi gives free play to his multi-faceted imagination, by discovering unusual associations between music and painting. Both the music and the painting originate in a series of sound and figurative relations that the composer calls "Phono-chromatic scales"; what happens in the score has a direct equivalent in the painting, proceeding autonomously in the time and sound space.

Josué Gutiérrez (Translation: Susan Eggleton)

Amazon

Amazon