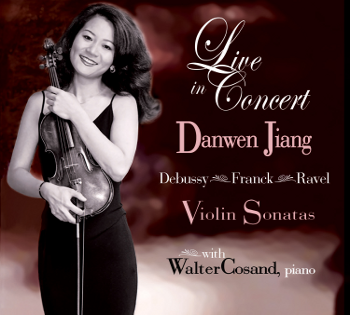

This is a positively luminous recital of three French sonatas played here with a true understanding of the style and a genuine symbiosis between violinist Danwen Jiang and pianist Walter Cosand, both outstanding performers and both on the faculty of Arizona State University.

Each of these works is a well known violin staple and this is a beautiful program of these gems of the repertoire. The Debussy is the shortest of the three and is, in some ways, unique among the composer’s output. This work was supposed to be the third in a series of six chamber sonatas. However, it ended up being the last work Debussy completed before his death. Interestingly, Debussy was not entirely satisfied with the work, finding it an uncomfortable (but ultimately very successful) combination of formal sonata structures and infused folk patterns. The first movement, Allegro vivo, is melodic and flowing with some interesting rhythmic patterns, but it really never rises to what most would consider “fast.” Therefore, Debussy did not find a need to include the usual slow movement. The second movement is an Intermezzo (“Imaginative and light”). It has a bit of a dance quality to it and a highly chromatic melody. The third movement Finale (“Very animated”) bothered Debussy the most. It is said that he found it difficult to write and to provide a suitable finish for it. Initially, the violin restates the opening theme of the first movement, with similar accompaniment. But, then, the violin breaks out into a bit of solo frenzy. The movement contains many wonderful quiet moments, but it ends quite dramatically and in a G major key, instead of the work’s predominant G minor.

Franck’s Violin Sonata is considered one of his masterworks. Composed in 1886, the Violin Sonata in A major is one of the finest examples of his use of “cyclic form”, a technique he had adapted from his friend Franz Liszt, in which themes from one movement are transformed and used over subsequent movements. The Violin Sonata is a prime example of this technique. Practically the entire sonata is derived from the quiet opening phrases of the first movement, which then evolve clearly and continuously across the sonata. The gently oscillating violin figure from the opening Allegretto ben moderato dominates the movement, and the markings Franck provided are insistent on playing molto dolce, sempre dolce, dolcissimo. The second movement Allegro, (passionato) changes things completely. Some have argued that this Allegro is the true first movement and that the opening Allegretto should be regarded as an introduction of sorts.

The Recitativo-Fantasia is the most unusual movement in the Sonata. A quiet piano introduction offers a variation of the passionato opening of the second movement. The violin makes its entrance with an improvisation-like passage (the “fantasia” of the title), and the entire movement is very open in both structure and expression. The finale, Allegro poco mosso, is, essentially, a canon in octaves, with one voice following the other every measure. This canon recalls the sonata’s opening theme, and as this movement progresses there are thematic elements from earlier movements. The work ends in large, dramatic fashion.

Maurice Ravel wrote the Sonata for Violin and Piano rather late in life and, as a result of ill health, it took four years to complete. His earlier more “obvious” connections to Impressionism are not present in his later works, this Sonata included. However, the Violin Sonata has many clearly impressionistic moments. On his approach to writing for two solo instruments (in his mind),Ravel is quoted as having said, “In the writing of the Sonata for Violin and Piano, two fundamentally incompatible instruments, I assumed the task, far from bringing their differences into equilibrium, of emphasizing their irreconcilability through their independence.” What he perceived as “irreconcilability” certainly comes across as symbiosis. The first movement, Allegretto, is written in traditional classical form. The violin and piano alternate in presenting the main musical ideas. There are some counter motives that reappear later in the work. The second movement, Blues: Moderato, incorporates the technique of bitonality but takes its main inspiration from the “blues”, as Ravel had a great fondness for. In this case, the bitonality was used to give each instrument a specific character. The blues style component gives the movement a bit of melancholy character. In particular, it is said he was trying to emulate a jazz saxophone “whining” between pitches within a melody. On the violin, slow ascents to a note create the desired exotic effect. The last movement, a Perpetuum mobile, is a tour-de-force for the violinist. A string of propulsive uninterrupted 16th notes drive the work to its exuberant and breathless conclusion.

Both Danwen Jiang and Walter Cosand are incredible, gifted performers with international reputations. They play with finesse and sensibility to the form of these master works that rates with any performance of these works I have heard. The natural ensemble playing between Jiang and Cosand exudes a true symbiosis with a unified approach to phrasing and musical styles. This is really one of the nicest and most rewarding violin sonata discs I have heard in awhile; these are performers who need to be heard and known with the highest regard.

Published on July 18, 2013

Daniel Coombs

Audiophile Audition

http://audaud.com/?p=32418

Amazon

Amazon