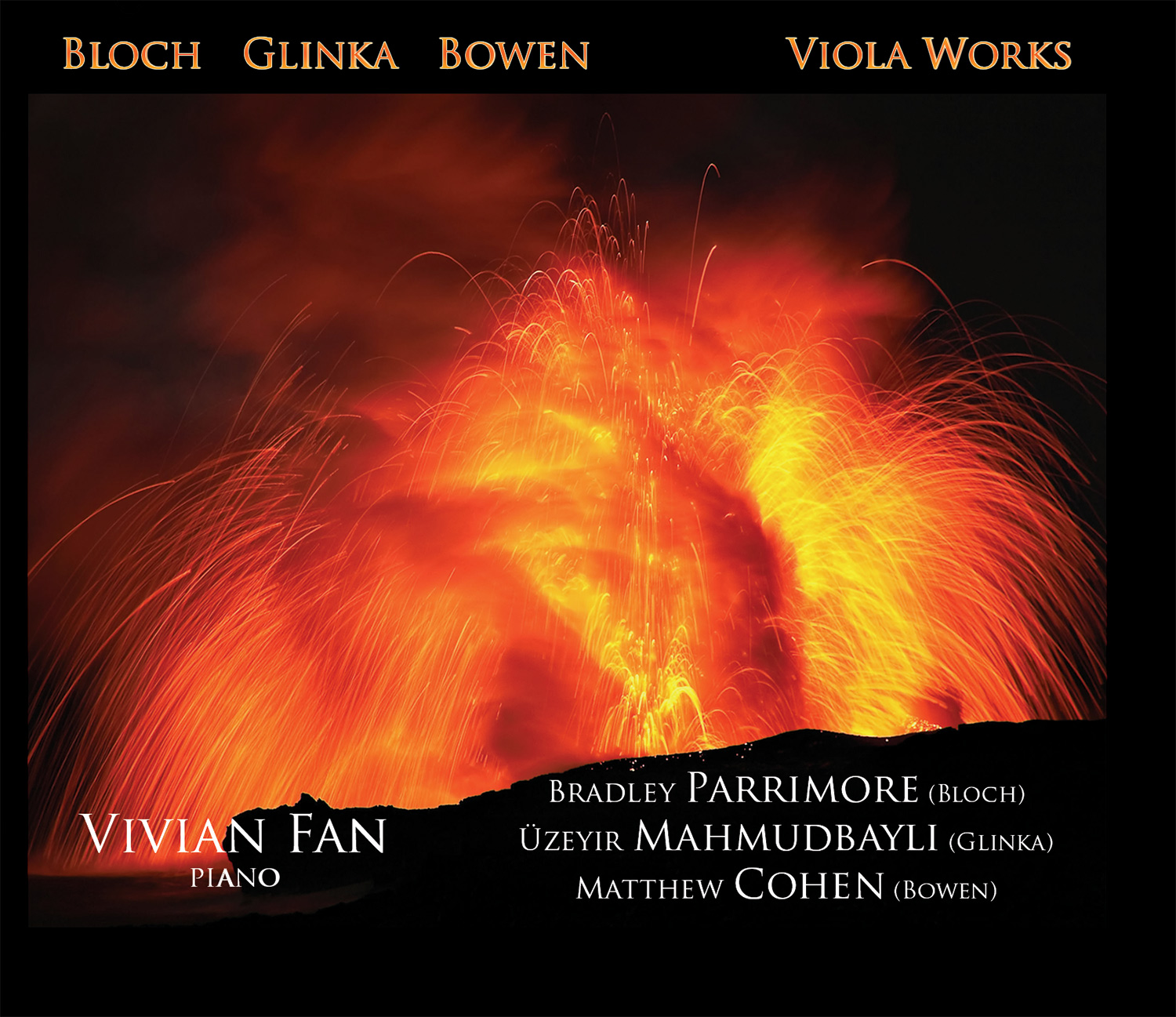

PROGRAM NOTES

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959)

SUITE FOR VIOLA & PIANO (1919)

Ernest Bloch is a composer best remembered for his fascination with Jewish music. While not all the music he composed was in this vein, many of his most often performed works are so, including Schelomo for cello and orchestra, from the composer’s self-described “Jewish Cycle,” and the Baal Shem Suite of 1923 for violin and orchestra. Born to Jewish parents in Geneva, Bloch studied the violin from age nine, showing prodigious talent. He moved to Brussels at the age of sixteen to study with the renowned violinist Eugène Ysaÿe.

It was as a composer, however, that Bloch found his calling. He wrote his Suite for Viola and Piano in 1919, the first piece he composed after moving to America, and he entered it in a chamber music competition sponsored by Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. The Suite won the first prize, narrowly surpassing Rebecca Clarke’s Viola Sonata, thanks to a tie-breaking vote cast by Coolidge herself. Bloch wrote to the French violist Louis Bailly, who gave the Suite’s premiere, describing his fondness for the instrument: “The viola has always been one of my favorite instruments. It can express the whole range of feelings and passions with an intensity and colour that very few people imagine.”

Bloch wrote lengthy notes on the Suite. What follows is an introduction describing its original programmatic background:

It is rather a vision of the Far East that inspired me: Java, Sumatra, Borneo - those wonderful countries I so often dreamed of, though I never was fortunate enough to visit them in any other way than through my imagination. I first intended to give more explicit - or picturesque - titles to the four movements, as: I. In the Jungle; II. Grotesques; III. Nocturne; IV. The Land of the Sun. But those titles seemed rather incomplete and unsatisfactory to me. Therefore, I prefer to leave the imagination of the hearer completely unfettered, rather than tie it to a definite programme.

The first movement begins with an eerie, discordant declamation in the piano, which Bloch describes as “a kind of savage cry, like that of a fierce bird of prey.” The mood is dark, strange, and restless; one can easily see why Bloch initially titled this movement “In the Jungle.” The initial entrance of the viola is improvisatory and wandering. The main body of the movement is a faster Allegro, with a ceaseless, urgent energy that is almost manic at times, interspersed with exotically lyrical, expressive interludes. The final section features a recapitulation of the opening viola motive, but with a gentler accompaniment in the piano. The movement ends with a final high F-sharp in the viola, slowly dying out in a measure of peace.

The second movement would be the scherzo movement in a traditional sonata or symphony. Aptly marked Allegro ironico, this is indeed a scherzo, but of a rather different sort. Bloch wrote of this movement: It is a curious mixture of grotesque and fantastic characters, of sardonic and mysterious moods. Are these men, or animals, or grinning shadows? And what kind of sorrowful and bitter parody of humanity is dancing before us - sometimes giggling, sometimes serious?

Again, Bloch’s initial subtitle of “Grotesques” is spot on; whereas scherzo, meaning “joke” in Italian, was traditionally a fast, high-spirited dance, here the joke is delivered with a rather twisted sense of humor. A slower middle section that takes the place of the trio in a scherzo or minuet quotes the rising viola motive from the beginning of the first movement. The scherzo returns at the end of this short movement, building quickly and ending abruptly.

The third movement is the shortest of the Suite, and is by far the most tranquil, although still with plenty of mystery and exotic shadings. Bloch wrote of this movement:[The third movement] expresses the mystery of tropical nights. I remembered the wonderful account of a dear friend who lived once in Java - his travels during the night ... arrival at small villages in the darkness ... the distant sounds of curious, soft, wooden instruments with strange rhythms ... dances, too ... Many years have passed since my friend told me all this; but the beauty and vividness of his impressions I could never forget - they haunted me; and almost unconsciously I had to express them in music....

The fourth movement, a joyful, exuberant dance, provides startling contrast to all the brooding, enigmatic turmoil of the previous movements. Bloch describes it as “... probably the most cheerful thing I ever wrote.” One can easily see why; there is no trace of the shadow that has hung over the rest of this massive output. A more lyrical yet no less intense middle section is filled with themes and motives from the first two movements. The end of this movement features the return of the beginning of the first; Bloch has taken us on a journey through the Far East and we have returned from whence we came, albeit a little more well-traveled.

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1804-1857)

SONATA FOR VIOLA & PIANO IN D MINOR (1824-28)

Mikhail Glinka holds an important place in music history; he is widely considered to be the father of Russian classical music and the founder of the nationalist school of Russian composers. His music had a profound influence on “The Five,” the group of Russian composers including Alexander Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Modest Mussorgsky, who followed Glinka’s example and made their goal to establish a distinctly Russian music rather than merely imitating the example of Western Europe.

From an early age, Glinka was fascinated with music. As a young boy, he frequently heard the bells of a nearby church ring in a strident, discordant manner. This influenced his harmonic preference accordingly, and he easily moved beyond the monotonously smooth, consonant harmonies of his contemporaries. In 1830, Glinka traveled to Italy where he lived for three years, and subsequently spent time living in Berlin and Vienna. In the course of these stints abroad he studied with various notable teachers of composition and counterpoint and was introduced to great musical personalities such as Mendelssohn, Berlioz, and Liszt. Eventually, he realized that his life’s calling was to do for Russian music what Bellini and Donizetti had done for Italian music, and he returned to Russia.

Glinka’s viola sonata is not one of his better-known works, nor is it an epic work on a grand scale. Rather, it is a little-known musical gem tucked away in an obscure corner of the viola repertoire, occasionally brought out to great effect as a charming tidbit of musical history that it is. Glinka began the work in 1824, when he was only twenty years old, and stopped once the first movement was complete. He did not return to it until 1828, at which time he mostly completed the second movement. He planned to write a third movement, a “Rondo,” which never materialized into anything but a few brief sketches. Despite his abandonment of the Sonata he wrote fondly of it in his memoirs, stating that he considered it the best of his pre-Italian works; he even mentions having played both the viola and piano parts on separate occasions. The first movement begins with an ascending four-note theme in the right hand of the piano, coaxed along by urgently flowing eighth notes in the left hand. The first phrase is in the traditional eight bars, after which the viola enters and takes up the theme. This movement is both young and fresh, and yet startlingly mercurial and multi-faceted for a twenty-year-old composer who had never left Russia. Elegant, sorrowful, stormy, and passionate by turns, the young Glinka shows he is no small force to be reckoned with.

The second movement, while written only four years later, betrays fundamental changes in Glinka’s compositional prowess; its depth and maturity simply outstrips the first movement. It is highly reminiscent of early Mendelssohn - not surprisingly as the two were contemporaries. As such, the work as a whole has an altogether different feel than the traditional sonata form in which the work was intended. Rather than a complete three or four movement work with an overarching structure, this is more like a prelude or overture to a more musically substantial romance or nocturne. Sweetly expressive and flowing lines are exchanged between the viola and piano as gently as a lullaby. The middle section is shocking in its contrasting passionate turbulence. Calm returns once more, and the movement ends as simply and gently as drifting off to sleep. While one might understandably wish that Glinka had concluded this work with a third movement, it somehow doesn’t feel at all incomplete; Glinka has left us with a work that is powerful, touching, and profound.

York Bowen (1884-1961)

PHANTASY FOR VIOLA & PIANO OP. 54 (1918)

York Bowen was a virtuoso pianist, composer, teacher, and an accomplished player of the horn, viola, and organ. Hailed by no less than Camille Saint-Saëns as “the most remarkable of the young British composers,” Bowen achieved success as both a pianist and a composer early in life. His symphonic poem The Lament of Tasso, Op. 5, was conducted by Henry Wood when Bowen was only nineteen. The same year, Bowen was invited to perform his first piano concerto at the Proms, again under Wood’s direction. Bowen had a large compositional output of symphonic and chamber music, including a great number of works featuring the viola, the tone quality of which he considered superior to that of the violin. One cannot begin to discuss Bowen’s viola compositions, however, without mention of the English violist Lionel Tertis.

Tertis is considered today to be the founding father of the modern viola school. At a time when aging orchestral violinists were often sent to “retire” in the viola section and the concept of a concert featuring the viola was laughable, he single-handedly ran an extremely successful and aggressive one-man campaign to establish the viola as a viable solo instrument. In addition to his legacy as a performer, Tertis is responsible for the existence of practically the entire body of English music for the viola from the first half of the twentieth century - as he alternately inspired, cajoled, or downright bullied most of the young composers of the day into writing music for him. In the case of Bowen, however, little persuasion was needed; Bowen became one of Tertis’ main recital partners throughout his career, and Bowen wrote every one of his many viola works for Tertis, including a concerto, two sonatas, a Rhapsody, and numerous smaller works, as well as the Phantasy featured on this recording.

Dated May 31, 1918, the Phantasy in F major, Op. 54, like all of Bowen’s works for viola, is highly virtuosic and expressive, and exploits the full range and capabilities of the instrument. The work is set on a grand scale and is in multiple sections. It begins with the unaccompanied viola in its deepest and softest range and soon blossoms into warmth and richness with the entrance of the piano. This introduction soon gives way to a lively, dance-like interplay between the two instruments in 6/8 meter. The opening theme returns in the next section, a poignant and expressive episode in key of D Major; this is Bowen at his most melodic and rhapsodic. The dance returns again before the emotional heart of the piece, a yearning, searching song that reaches ecstatic heights of passion. The finale is joyous, playful, and above all exciting. Quick wit and blistering speed abound as the music works itself into a frenzy. The piece ends with superb drama and stratospheric emotional heights, resounding and triumphant.

Matthew Cohen

Amazon

Amazon