| Physical CD 16.99 US | Digital Download | |

|  Amazon Amazon |

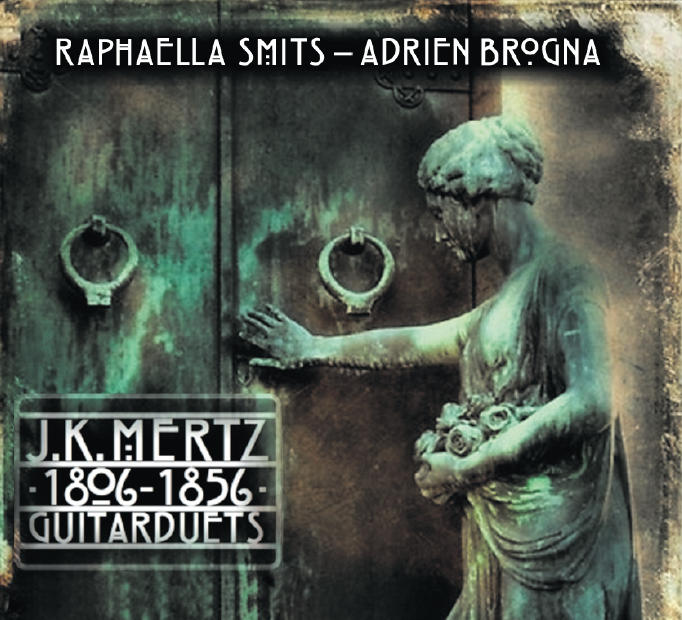

| Fantaisie Hongroise, Op. 65, No.1 | 01. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Fantaisie Hongroise, Op. 65, No.1 8:03 | |

| Fantasie Originale, Op. 65, No.2 | 02. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Fantasie Originale, Op. 65, No.2 7:35 | |

| Le Gondolier, Op. 65, No. 3 | 03. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Le Gondolier, Op. 65, No. 3 4:37 | |

| Ständchen, Schwanengesang, D 957 No. 4 | 04. | Franz Schubert: Ständchen, Schwanengesang, D 957 No. 4 4:47 | |

| Romanze, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 No. 10 | 05. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Romanze, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 No. 10 3:01 | |

| Gondoliera, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 | 06. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Gondoliera, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 4:51 | |

| Lied Ohne Worte, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 No. 11 | 07. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Lied Ohne Worte, Bardenklänge, Op. 13 No. 11 4:44 | |

| La Rimenbranza | 08. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: La Rimenbranza 6:55 | |

| Der Leiermann, Winterreise, D 911 No. 24 | 09. | Franz Schubert: Der Leiermann, Winterreise, D 911 No. 24 4:17 | |

| Elegie | 10. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Elegie 9:02 | |

| Nocturne, Op. 4, No. 1 | 11. | Johann Kaspar Mertz: Nocturne, Op. 4, No. 1 3:23 | |

| Aufenthalt, Schwanengesang, D 957 No. 5 | 12. | Franz Schubert: Aufenthalt, Schwanengesang, D 957 No. 5 5:16 | |

Total Playing Time: 1:06:31 | |||

raphaella_smitsvienna_concert.pdf *

raphaella_smitsvienna_concert.pdf * guitare_classique_review.pdf

guitare_classique_review.pdf

About performing art

As a performing musician, you are a translator. As a translator you work with at least two languages: one in which the work in question is written and the other in which the translation must be done. We have to understand that second language thoroughly, not just the alphabet, the words, and the phrasing, but above all the deeper meanings.

We try to hear what a composer intended, what he would have heard in his inner ear, what he tells us through his music, and what we can make the listener learn from the rhetoric in the music. This will most obviously be possible with the correct instrument, whatever this is. It must be the instrument that allows you to write perfectly the music in the mind of the listener.

In the nineteenth century there were many different types of guitars. Some builders were known for their experimental constructions; others would maintain the tradition, just as we have it nowadays.

So what is the most correct instrument to perform (contemporary) music? It will be the one that allows us to serve most faithfully the thoughts of the composer.

J. K. Mertz played different guitars, having from six-to-ten strings. Reading the letters by Nicolai Petrovich Makaroff (1810–1890), we discovered how difficult it was (and still is) to find the best instrument, the most suitable and available one.

Great guitar builders such as Stauffer, Scherzer, and Fisher were all devoted and well-known by many performers in Vienna and beyond.

My guitar has no label. It’s not a typical Viennese instrument, but a French-made guitar from the time of Mertz. Just as it was common practice in those days, luthier Bernhard Kresse added two low basses, which gives me the opportunity to play the music written for more than six strings, as it is the case for several works of Mertz. In the meantime, it gives the instrument and the music a resonance and depth that perfectly serves the composer’s intentions.

Mertz himself played masterfully, mainly solo works of his own, but also chamber music. Some of his most complex compositions could only be published posthumously because he was convinced that most players would fumble, being incapable of producing the right sound for his work. In addition, publishing houses would find his music too virtuosic for the average guitar player, and therefore impossible to sell.

As Makaroff describes in his Memoirs (© 2016 Matanya Ophee): “He [Mertz] was indubitably the best of German guitarists … power-energy-feeling-distinctiveness, expression and self-assurance.” But Makaroff was rather critical about the (i-m) perfection in Mertz’ playing, with growing respect for the composer, as well as for Mertz himself.

He listens with bliss and reports: “rich substance, profound knowledge of music, excellent design and development of an idea, completeness of harmony, clear melody flowing above the chords and arpeggios, brilliant but not vulgar effects …”

For me, the quality of Mertz’ compositions match the works of the greats such as Chopin, Liszt, Schumann, and Schubert. Beyond that, he had his own language: beautiful melodies, fantastic cadenzas, virtuosic passages and with that ever-present Romantic soul.

The vocabulary with which he wrote his works often shows melancholy, softness, broken chords, fast passages and a clear polyphonic way of thinking. He writes orchestrally or pianistically, not in the styles of other typical and mundane nineteenth-century guitar music.

I've been interpreting Mertz's work for many years now, but the selection for this recording gives a broader picture of his music and informs more about how he played, and how he intended it to be played, I think.

About this recording

For this recording, I’m using gut strings - expensive, difficult to get, not always in tune, quickly worn out, and consequently a terrible sound as a result. But: with good care, they result in fast projection, great tuning, and a transparent, clear and elegant sound. Moreover, and most interestingly, is the need to use a different technique, which sometimes leads to a very remarkable, slightly different interpretation. This was a discovery in beauty and understanding; the instrument is in balance, and so is the music. This results in the player's technique in service of the language, a language that is the composer's speech. I sincerely hope that I have succeeded in this intention.

Mertz is one of the great guitar composers, undervalued due to lack of understanding and the necessary virtuosity, and a lack of freedom and a poor imagination. Mertz' important contribution to the guitar repertoire deserves all the attention it can get.

The addition of Mertz’ transcriptions of some Schubert Songs from Schwanengesang indicates his musical sympathy for the latter. As for Der Leiermann from Winterreise, it fits so incredibly well that one would believe it was written especially for guitar, an instrument that Schubert loved very much. I could not resist presenting my own version of it.

All these works were adapted for my eight-string Mirecourt guitar of 1827.

Strings 1 and 2, Kürschner gut; 3, Savarez Alliance; 4, 5 and 6, Fisoma silver wound basses; 7 and 8, Labella Argento pure silver.

The collaboration with Javier Salvador was once again inspiring, very professional, and with a lot of understanding.

- Raphaella Smits